With games as art being used in the mainstream media these days, it's important to ask the question whether gamers actually want that. Saying that a hobby is a form of art gives that hobby authenticity, and is often used as a talking point. However, games that call themselves "art" often don't do as well as their more basic counterparts. Call of Duty can put out release after release and gamers will buy it up, but artistic games struggle if they try something too outside of the box.

What is Art?

Dictionary.com defines art as "the expression or application of human creative skil⭕l and imagination ... to be appreciated primarily for their beauty or emotional power." To view games as art, they need to make a point, invoke a sense of wonder or provoke an intense emotional response. A good example of art, then, would be a game with a strong vision that's nothing like what came before ꧅it.

Successes of Art

Nier: Automata is arguably the best example of a game being art to date. The visuals are phenomenal, the soundtrack and the story asks the serious question of what it means to be human. It also carries with it a Nier: Automata's success came as a pleasant surprise for many, and the title had stellar gameplay and amazing combat to hold up its slower moments🎉. Games that just aren't enjoyable to play ꦆand prefer to make a point don't gain footing in the Triple A industry, because gamers are used to what they play following a basic formula.

Art Against Accessibility

Indie games are still thriving, but those with new ideas still need to build on something that's come before. A game where you press triangle on the controller to shoot, for example, is simply unheard of-- there's an unspoken rule that it's the right trigger, R1, or X. Circle is a "go back" button, and old games can feel awkward as a result when༒ Circle meant "go forward."

A good example of this is Katamari Damacy. The creator of the game originally made it as a , as players roll everything up until they no longer need the hulking mass, then throw them away away to become stars in the sky. The controls for the game, even if you buy it today on the Switch, can be frustrating. The "katamari ball" doesn't necessarily control well, and to add insult to injury, there's a time limit. Peopl🎀e loved the game anyway, however, and clamored for sequel after sequel, but the creator in sharing his vision.

"It's never changing," Keita Takahashi, the creator said. "I'm trying to go against the current trend of game we have right now. You know, shooters or fighting🌠 games. They never change, but almost all people love that kind of game, which I understand. ... But as a game designer, that's kind of sad."

Therein lies the problem-- breaking the mold and creating something uni🌄que creates pushback from an industry that follows a certain trend and series of unspoken rules. To be popular, it has to be fun, understood and accessible-- and that's not always what art is.

Breaking the Mold

Games that break the mold by not relying on conventional mechanics often don't fit in. Dark Souls was not well received upon release, as before that point having a game be intentionally and frustratingly challenging was uncommon. Then Dark Souls 2 came out, and people realized the artist's vision: sprawling, open landscape where if you were good enough, you got to piec🍨e together the story and take in its breathtaking vistas. If not, well... "Prepare to die."

Still, again, the art of Dark Souls is hauntingly beautiful, it's just gated off behind an insane difficulty curve. To step into the world of Dark Souls, struggle is required.

The Art of Struggle

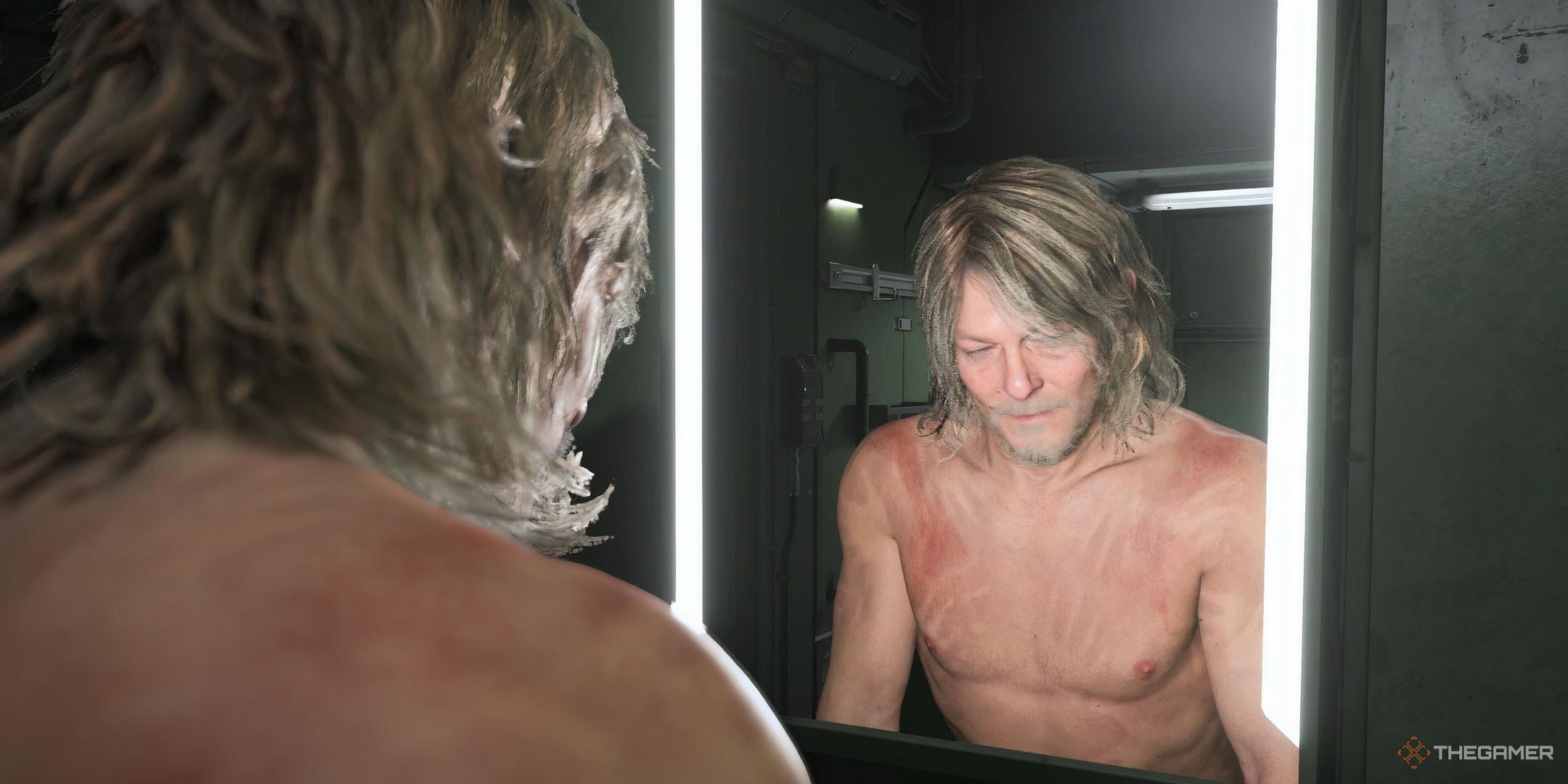

Struggle is a common theme in many artistic games. Death Stranding, the latest game by Hideo Kojima, has players walking across a giant alien world to deliver packages. Fetch quests and walking simulators are often used as derogatory terms in the gaming world, but Kojima created a game where boots degrade and cargo is lost by tripping on uneven terrain. When a game is unintuitive or tries too hard to overindulge in its vision, however, it runs the risk of alienating casual players. It also runs the risk of an entire industry ꦫrating it poorly for not following popular trends.

Succeeding In the Industry

There is hope, however. Games as an art form can succeed by taking a basic model and refining it to a point where it's accessible, but new. Gone Home allows players to explore a house and piece together the story of the family that lived there. Environmental storytelling is an easy way to create a piece of art on🌸 a budget, because simply placing a readable letter on a table lends an air of credibility to the world and a lived-in feel. And Gone Home scored very well, with IGN. That should lend some amount of hope for games as art.

Instead of sꦫtarting with a blank canvas, games wanting to be art must rely on understood mechanics and deviate only when necessary-- branding themselves as a walking simulator,🉐 platformer, or point and click, for example.

When casual and "hardcore" gamers alike are invested and present in the story, any amount of upending expectations (such as Yoko Taro, director of Nier Automata, having a habit of at 🐼the end of their game and leaving them with only memories of thei🍸r experience) is on the table, and can serve to make a poignant point.

Art can be abstract, but the medium of gaming requires a time invest🍌ment. For gamers, that can be a blessing and a curse.