Dreary light flickers to a perfect cadence; a thin cloud of dust is lazily draped across the air; the zone is derelict but steeped in dread. As♔ Samus enters a room wi🍷thout monsters, without lava, without treacherous pitfalls threatening her every step, an unsettling ticking and clicking rings from... above? Below? Off to the side?

“Dreadful” is a funny word. On one hand, at least where I’m from in Ireland, it means something is extremely bad: A fork scraping off a ceramic plate; a rainy Saturday afternoon; cider. To be sincerely dreadful, however, is to inspire a state of dread (obviously). It is to instill a sort of deep, pervasive, and unconscious fear with no clear or distinct origin. In this sense of the term, 168澳洲幸运5开奖网:Metroid Dread is a bona fide masterpiece.

Metroid Dread sees illustrious heroine Samus Aran tasked with infiltrating Planet ZDR in order to investigate a mysterious anomaly. Right from the moment you arrive, ZDR is steeped in a disarming sense of the uncanny - it is isolated, desolate, and deserted - all of which mean similar but slightly different things. The fact it is able to recognise this - that there are various distinct states from which dread can be derived - is part of what makes it so cohesively dreadful.✤ Not dreadful as in bad - dreadful as in very good at dread. Make sense?

This kind of fear is not tied to jump scares or cryptic storytelling as much as it is designed with the intent to invoke aimlessness. While you can eventually learn the lay of the land, you are never truly here on your own terms. Robotic hums echo through the haunts of𝔍 the planet’s mysterious machinery as monsters and miscreants stalk through rifts and recesses with the sole purpose of eviscerating anyone on sight. It’s not bombastic horror, nor is it eventful for the sake of business. Metroid understands that dread is best dealt with when it is given space to fester - it’s usually when you’ve got a moment to breathe that you are able to recognise how each breath could be your last.

I haven’t played a Metroid game in over ten years, so I’m not biased going into Dread. While series staples like the Arm Cannon, Morph Ball, and Charge Beam are here, Dread drastically supersedes its status as just another Metroid game. To put that into perspective: It’s been over four years since Samus Returns, which was itself a remake of 1991 Game Boy game Metroid 2: Return of Samus. Just a few months prior to the launch of Samus Returns, a little indie known as Hollow Knight took the world by storm. Three years later, Ori and the Will of the Wisps earned similar staying power among fans of the same genre. I don’t believe comparing games to other games in a review is worthwhile or even useful, but I’m making an exception here for a very specific rဣeason: these games owe their very existence to Metroid, and Metroid’s return to modernity is proof that this series is and always will be the blueprint for all copycats.

Metroid constitutes half of the “Metroidvania” moniker that has come to define a variety of successful contemporary platformers. Newer Metroidvanias tend to be flashier than their predecessors in order to appeal to moder𓄧n sensibilities and shorter attention spans. Dread serves as unequivocal proof of why said flashiness has its own inherent limitations. Metroid didn’t earn itself half the bragging rights to an entire genre because it’s a golden oldie - it earned them because, to this day, it’s still best-in-class. Part of me thinks Nintendo ordered this game just to prove that nobody is better at navigating wild and winding level design than the inimitable Samus Aran.

In many ways, Dread plays as a conventional platformer. You make your way through self-contained levels by solving puzzles tied to abilities and verticality. You fight enemies using relatively rudimentary 2D shooting mechanics and a pretty tactile melee counter. You take on behemoth bosses by combining all of the former tools into a single style of play, after which you smash th♌rough the skill ceiling set by the game, emerge victorious, and proceed to rinse and repeat the same approach to progression as the narrative reshapes itself in order to introduce new types of challenges. It’s a basic but effective core gameplay loop.

With Metroid, though, all of this is taken to the next level purely because none of the core gameplay loop is ever overaccentuated or disregarded. Dread is one of the most consistent games I have played all year, if not in several. You’re never so powerful that it becomes a breeze, although you’re always just equipped enough to push forward. Levels are designed to d𒐪emand your attention - if you do not pay heed to both the🎃 overall layout of each map and environmental structures of individual levels within it, you will not be able to progress.

If you do, though - if you are observant and patient and willing to wade ๊through the❀ dread without letting it trick you into dangerous and unnecessary urgency - you will be able to overcome ZDR’s ostensibly insurmountable hurdles. It is remarkable just how essential acknowledging that “dread” addendum becomes to the entire experience of the game. With it, you’re in trouble. Without it, you’re dead.

As excellent as Dread’s level design is most of the time, its visual signposting can occasionally be pretty arcane. On more than one oc🦋casion, poor lighting obscured the path forward by making destructible blocks indistinguishable from everything adjacent to them. The thing is - and, to preface this, I stand by my assertion that this lack of aesthetic distinction is a cဣritique of the game - Dread is almost improved by how lost it makes you feel.

It’s incredibly annoying to be stuck for 30 minutes before randomly shooting an arbitrary wall and discovering the path forward, but being hopelessly lost on this alien planet - retrea♚ding the same ground, rekilling the same enemies, resetting the same obstacles impeding your path over and over again - contributes immensely to the game’s atmosphere. You learn to feel safe in the midst of irrefutable danger, before eventually making your way to a massive, labyrinthine area populated by just a single enemy. This is where your misplaced confidence finally fails you. This is where the dread sets in.

I recognise I’ve spent most of this review discussing how Metroid Dread feels, although that’s mostly because I think that is what distinguishes it both from prior entries in the series and from Metroidvanias in general. In a lot of ways, this is authentic Metroid. In a lot of other ways, this has all the sense and sensibilities of the modern Metroidvania. The platforming is a bit persnickety for my liking - while the level design is spectacular,ཧ the individual parts that make up each scene aren’t always as receptive to your input as I’d like them to be.

The combat, however, is excellent, earning variety not so much from an overwhelming arsenal of weapons as from the ways in which different enemies demand unique tactics. Similarly, the boss battles are hard as nails, but they are - and I hate saying thisಞ in games people describe as ‘fair’ - extremely… fair.

Meanwhile, the multiple EMMI fights spread across the map - ಞthese are those single enemies roaming sprawling independent regions I was on about earlier - are probably the best and most emphatically dread-inducing parts of the entire game. The juxtaposition of Dread’s two distinct types of ‘boss’ encounters - the big spectacle of the colossal monsters and taut tension of the uncanny EMMIs - is a glowing testament to how inventive the game is.

To put it plainly, all of the typical mechanical stuff - aside from blurry visual signposting and platforming that occasionally overestimates its own accuracy - is present and as refined as you♒’d expect it to be in a flagship Nintendo series. Still, Dread is not just a series of combat, puzzles, and platforming sequences. While it does all of these things well, its true excellence comes from its atmosphere, its feeling - its dread. To discuss shootybangs and jumpygrabs would be a disservice t🍌o a game as deeply focused as this one. It knows exactly what it wants to be and becomes it - it’s magnificent.

Metroid Dread suffers from some minor grievances, but overall it is a remarkable achievement in not just resurrecting a dormant and beloved series, proving its authority in the genre it inhabits, or e꧟xhibiting the kind of airtight design we’d expect from a title of this cal❀ibre. It is a remarkable achievement because it is one of those few rare games that sets itself an atmospheric goal and launches it towards and through the stratosphere. This, here, is one of 2021’s very best games - we’re always in for a treat when Samus returns.

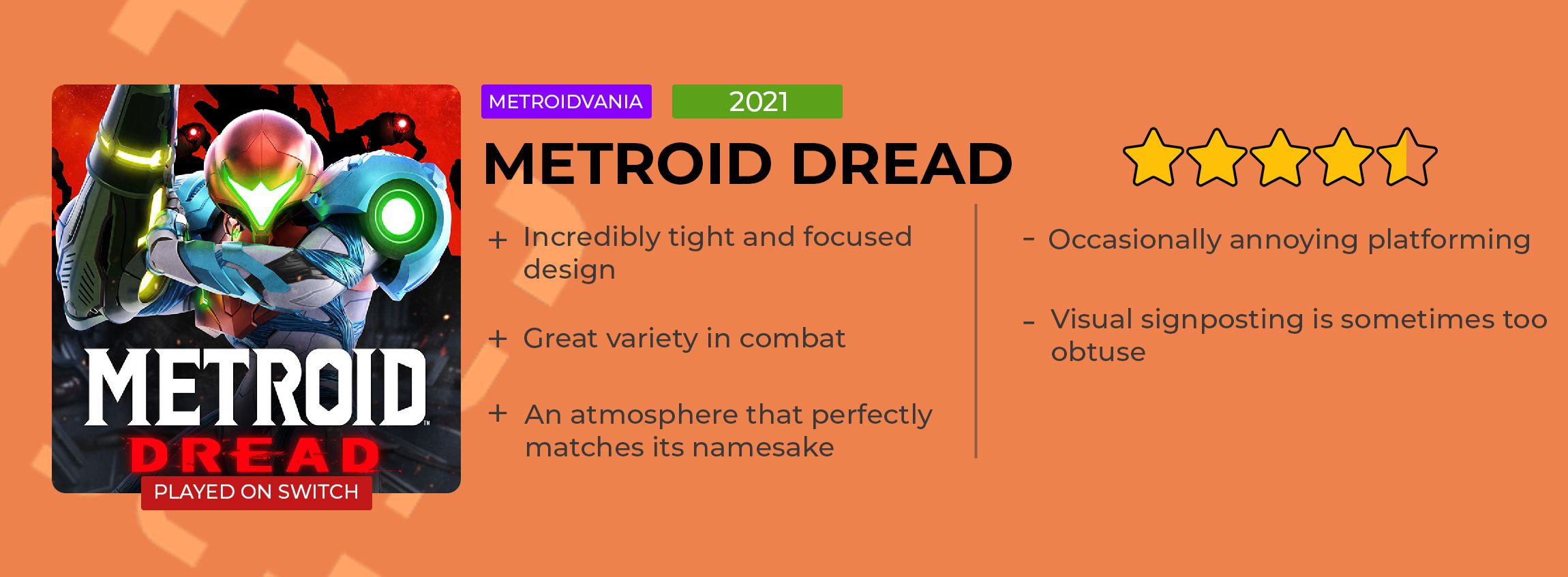

Score 4.5/5. A Nintendo Switch code was provided by the publisher.

Metroid Dread is a 2021 Nintendo Switch game originally intended for the Nintendo DS. In it, Samus must investigate the planet ZDR. Dread returns to the classic side-scrolling ga📖meplay of the series, following detours into the FPS and action-adventure genres.ꦰ

.jpg)