The Girl From The Sea isn’t afraid of being a queer story. It’s a tale that aims to explore the themes of innocen💎t youthful love while not shying away from the messy reality of coming to terms with one's own identity. We all grew up with misconceptions about who we are supposed to be, abiding by internal expectations that held us back from being happy, content, and willing to push for an existence that makes us want to enjoy life. For people in the LGBTQ+ space, that journey is a continuous one with its fair share of trials and tribulations. But keep on fighting, as I am, since the end result will be worth the battle.

Molly Knox Ostertag is an author, writer, and illustrator who isn’t afraid to explore such ideas, and I recently caught up with her to share queer stories and talk about her career as a proud lesbian woman pushing for new, groundbreaking stories in a number of spaces. Having worked on webcomics, graphic novels, and shows s🧸uch as The Owl House and Star Vs The Forces of Evil, Ostertag has cemented herself as a no🌺table voice in the queer community that many look up to. It’s a funny position to end up in, given this medium of work is one of the things that helped her embrace her own identity.

“When the first one was released I wasn’t out yet [as a lesbian],” Ostertag tells me, referring to The Witch Boy trilogy of graphic novels. “But I started to realise I had a pull towards 🐬these communities and wasn't sure what to do with it. When I was a kid I was definitely a tomboy who went against certain gendered norms and thought gendered expectations were really oppressive. So I wanted to push back against that.” The Witch Boy follows a young androgynous boy called Aster who wishes to become a witch, a role which is reserved for female members of his insular society of friends and family. He is destined to become a shapeshifter like the other boys, and any form of rebellion against this is met with disgust. It’s a metaphor for so many queer experiences, having to conjure up the bravery to go against what’s expected of you. “There were a lot of stories when I was a kid about girls who dress up as boys and do boy things, like join the football team or something,” Osꦍtertag says. “I felt like there were not a lot of stories about boys who appear to be boys wanting to do girl things. That’s what sparked the original idea and I wanted to explore that.”

The Witch Boy has since become a🔯 bestseller and is being adapted into an animated film for Netflix by Minkyu Lee, previously known for his work on Big Hero 6, Frozen, and a number of other projects. Despite its continued success, this is a story that remains close to the hearts of many. “Writing, pitching, and drawing the first book saw me th🥀rough a lot of big changes in my life. I moved across the country, I came out as gay and met my partner - who’s now my wife,” Ostertag explains. “It was a really good book to be drawing at the time. It was really close to my heart and when it came to drawing the next couple of books, I knew I wanted to make it about the queer community and reaching out to other people you share that with, because it ended up being so important to me.”

For her next two books, Ostertag would place a deliberate focus on queer themes, but approached them in a way that younger audiences could easily understand. L🌸abels weren’t str♌ewn about the place, but the core messaging still bled through, evident in each and every panel and snippet of dialogue. Aster’s journey is a relatable one, regardless if you’re firmly in the closet or proudly out of it. “I really wanted to present these queer, non-heteronormative, non-cisgender identities, but avoid using labels around them, and kind of explore it for these fairly young children who don't maybe have the words yet, because I felt like when I thought about my childhood and thought about, like, identifying with queerness, the actual words were very scary,” Ostertag says. “I think there’s room for implied or contextual queerness that isn’t ready to fully declare itself yet, and that’s what I was really trying to explore with these characters. It’s been really lovely to hear from people who see Aster as a trans girl, or to some he’s genderfluid, while others view him as a gay boy. That feels close to my intention of wanting to make a story that is describing the experience of a young person before they quite know who they are.”

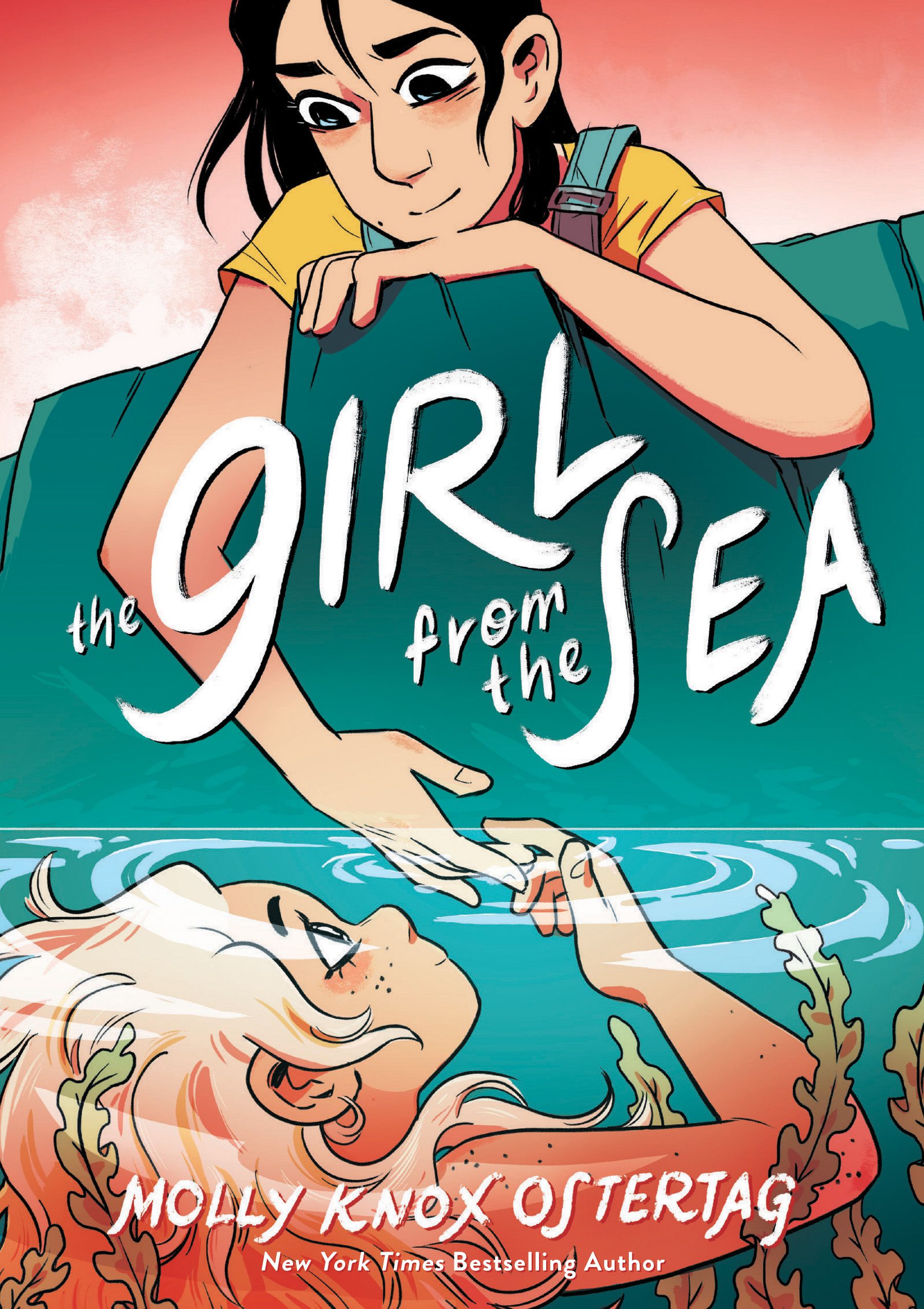

Th💛e Girl From The Sea aims to be a more honest expansion of these themes, no longer tip-toeing around the idea of queer representation so it’s trivial to digest for young audiences. Intended for a slightly older demographic, this adorable love story focuses on a teenager called Morgan who can’t wait to escape the claustrophobic island she was raised on. Her depressed and divorced mother, obnoxious little brother, and close group of friends are all facets of life she wants to leave behind - because in truth, they don’t really know her at all. In reality, she’s a closeted lesbian figuring out her identity, and before long a seal mermaid arrives and threatens to turn her life upside down - in a cute, wonderfully gay kinda way.

“I wanted to be very specific about the identities of these characters and their real world struggles, I didn’t want it to be a metaphor anymore,” Ostertag tells me. “She lives on this tiny island of Nova Scotia in the eastern province of Canada where my family would spend a lot of summers, so I wanted it to be set on this beautiful place. I can’t make it an auto bio so I invented some characters to live there, but the setting itself is very real.” This sense of reality isn’t just prevalent in the setting, it also manifests itself in the wider themes, and how queer people are often viewed as selfish for embracing their identity in fear it will inconvenience heteronormative society. Morgan is one such character: “She know’s that she’s gay,” Ostertag explains to me. “But she lives in this tiny town, has a close group of female friends, her family just went through a divorce so her dad is gone, 💟her brother is going through a bunch of issues, and she’s just like - it would be selfish to come out. But of course, as all well-laid plans do, it gets messed up.” Like real queer stories, this one is messy, but it’s also imbued with a genuine expression of love and affection that feels very, very real.

“Morgan meets a half-seal girl called Keltie,” Ostertag tells me with a grin, expressing a genuine love for these characters. “Keltie is a Selkie, meaning she can take off her sealskin and turn into a cute girl. And so she and Morgan fall in love and Keltie’s like ‘alright we are going to pursue our fortunes on the land!’ I think a lot of the books I read have a core scene where everything builds out from and the core scene here is Keltie coming out of the water and Morgan’s like “oh my god, no, we aren’t doing this” but Keltie is in love and wants to go on adventures.🐼 That fun dynamic is what leads to the rest of the book and it’s really fun. It's definitely maybe a little bit lighter andꦕ sweeter, but there’s some bittersweet drama.”

While The Girl From The Sea is primarily a fluffy story of adolescent gay romance, it also wants to tackle the struggles of queer identity, and how we can make a habit of hiding ourselves from the world in fear of rejection, of loved ones labelling us as a burden because we dare to be different. Morgan and Selkie’s blossoming love breaches upon this, two young souls from two vastly different worlds who happen to fall for one another. “I wanted the kiss to be in the first 10 pages and then the rest [of the book] is figuring out the repercussions of that and if they can be together, and if Morgan can stay closeted, and have this magical seal selkie girlfriend at the same time,” Ostertag says. “Morgan is the one I relate to the most because she’s trying to be everything for everyone. The parts of herself not for other people she’s putting in a box and dealing with it on its own. Now someone else is being introduced into the picture with Keltie being like “these parts of you are the parts that I love, are you going to put me in a box too?” Keltie isn’t used to the customs of our society, oblivious to the homophobic bigotry that can surface in the wake of leaving the closet. She’s blissfully in love, and this honesty is what leads Morgan to accept herself, even if it means pushing away those close to her. Sacrif🌌ices like this are common in real life, and Ostertag has explored them in her own personal, more mature projects outside of children’s fiction.

How The Best Hunter In The Village Met Her Death is a gruesomely hopeful story of coming out and realising that defining your own identity can be unfairly traumatic, largely because society has such strict, heternormative standards strewn across it. “That comic is probably my favourite thing I’ve ever done,” Ostertag states, our chat taking an emotional, almost tearful turn as she breaks it all down. “I had a very tumultuous coming out where I was with a man in this long relationship and I wa💛s starting to realize that certain people when they grew up think that they have to please other people. Other people’s feelings mat🐻ter more than mine, and that was always the way I thought, so why would I ever cause a fuss? If someone wants to be with me and they’re nice, then that is the person I should be with.”

The comic follows a hunter as she develops an irrational fascination with a magical beast on the village outskirts, a hostile creature who eludes capture at every turn. It becomes an impossible goal, one that the heroine obsesses over again and again until it almost ruins her. As the brief story concludes, the hunter allows the forest to consume her, transforming into a par🔯tner for the very beast she has tried so desperately to hunt. She has tried and failed to destroy her true self, a metaphor for a queer identity that so many people try to pu𓂃sh away in favour of a supposedly comfortable life. “The hunter is beloved by the village, she’s the wife, and she’s trying to do everything she can to maintain that because that’s what matters,” Ostertag explains. “Then she encounters this beast in the forest who is different than anything she’s seen before, she is drawn to it and doesn't know whether to kill it or become it. It’s definitely the work I made that comes from the most personal place and has gotten into some really raw feelings.”

I still doubt my queer identity, and sharing such stories was a cathartic exercise for me in a way I didn’t expect, knowing that other queer people experience such discoveries in an equally fractured manner. We should embrace how far we’ve come, regardless of how messy or seamless the journey has been. Ostertag closes off this train of thought as we move on from the hunter and onto something a little more cheerful: “I wanted to explore the incredible tension that I think a lot of queer people have when exploring identity and how it can almost feel like a selfish act. And it’s not, in reality, but there is a perception that you’re locked into what other people expect of you, and it was really about that tensioꦆn and fever about how can I have one part of my brain that’s thinking all these crazy things, and then have my life that is like, completely seperate?”

Ostertag couldn’t talk heavily on her work with The Owl House, a cartoon from Disney which has broken new ground in recent months by being one of the first children’s show to feature a queer romance with little to no compromise. Amity Blight is a young witch who develops a crush on Luz Noceda, a human who finds herself transported to a world filled with strange creatures and magical powers. It’s an adorable, progressive show that has amassed a huge fandom in recent years, beloved by a similar set of fans as She-Ra and The Princesses of Power and Kipo And The Age of The Wonderbeasts - two other shows that a🐷re proudly queer in their themes and characters. With queer media making such huge strides, I touched on Ostertag’s part in this, and her hopes for the future.

“I think we are getting better, and I think it’s just about having people who identify with theꦜ story being the ones to tell it,” Ostertag tells me. “Even when you have really well meaning, cis-het writers there’s a lack of interest a little bit? And that’s why we get stories like ‘oh they’re finally getting together but now the show’s over’, or ‘they’re finally getting together and now one of them has died tragically’. Even when they’re together, it feels like a heterosexual relationship, so I’m really just interested in [queer] stories by queer people. Small media does it better. Coming from the indie comics world, there’s so much incredible work out there. You see a zine online or at a comic fest and it’s just the most searing exploration of queerness that you’ve ever read. So the media is out there and people are telling the stories, but I don’t think it’s quite reached the mainstream yet, but we’re definitely headed in the right direction. I think all of my work is on a bit of a spectrum. The hunter comic is the most cutting and close to my heart and specifically for a queer audience, not pulling any punches and is about being very open and honest about the fear, ugliness, and weirdness of that experience. On the other end of the spectrum is my TV writing where I’m trying to tell these stories, but doing them in a way that studios will allow to exist, and kind of like how they can be the first step for people to be more accepting or to see themselves. It’s kind of fun to try and figure out how to do both things and be like here’s the real, raw stories and how do I tell them in ways that get a wide distribution?”

While huge fandoms have gathered around properties like She-Ra and The Owl House, Ostertag tells me 🌼that it’s important not to expect much from big companies, and how much the landscape has changed in just a few short years. “It’s been really cool to be in the animation industry and see how much has changed in the past five years when it comes to what we can have on screen,” Ostertag says. “There was a time really not that long ago when certain studios were like ‘it’s not appropriate to show same sex couples’, ‘it’s not appropriate to imply a character is trans’, and they were like ‘this does not have a place on children’s television’. That was not that long ago, so I think we are seeing a lot of growth which is cool, but I think it will always be met with opposition. I don’t think these kinds of fights are ever linear, so it’s important to keep fighting and keep pushing it. When you’re making work for a big company, if you stop being profitable to them they will stop supporting you. I’m always interested in connecting with other queer creators, even if they are making smaller stuff, then expecting stuff from the big companies.”

To wrap up our conversation, I ask Ostertag about what advice she would give young queer creators eager to make their mark in comics, animation, or writing - a space which is becoming more and more appealing with so many flagship names doing the rounds. Her answer was a surprisingly deep one. “Look at current pieces of media as stepping stones,” she tells me. “Steven Universe allowed She-Ra to happen. Noelle Stevenson was able to step onto that success and say ‘look how successful this show is, look what we could do, and let’s go even further’ in some respects. So I would advise young creative people to look at this work and think about how they can go even further.” Even though LGBTQ+ stories are becoming more commonplace in these spheres, they still abide by certain conventions, and Ostertag wants younger creators to embrace a more realistic expression of the queer experience. She brings up the wish to inꦿcorporate more butch lesbians into her work, going against the tall, long-haired attraction that defines so much queer media out there today. Work like this shouldn’t feel pressured into appealing to a straight demographic, it should be raw and unfiltered in its purpose. “I really want to see people exploring more complicated queer stories, for so long we’ve felt like we have to represent ourselves to straight, cis society and be like “here we are, look at us, there’s no conflict” and we’re all the most beautiful versions of these identities. I want to read the stories that are like “No, I’m ugly, I’m messy, I’m doing bad things, but that doesn’t mean my queerness is bad.” It’s still a complicated story, and that’s the kind of stuff I really want to see next.”

Finally, Ostertag emphasises the need for queer stories by queer people, and how cis creators have done a lot of damage to narratives that should have been championed by someone more capable. “There’s so many stereotypes or tropes that straight people and straight writers have almost ruined for us,” she explains. “I do want to see a story about a sam🔴e sex couple where one of them dies at the end, and it’s tragic and beautiful, but I don’t want it to be by a straight person. Like when I did my hunter comic, turning into a monster is almost a metaphor for being queer, and if a straight person did that it would be really really shitty.” Fortunately, perspectives are becoming more informed, with stories in games, film, comics, and so many other mediums welcoming queer stories in ways they haven’t before. The road ahead remains a long one, but the future is bright.

The Girl From The Sea Will Be Available On June 1st. You can check out all of Molly’s work over on her .