From the byzantine megastructures of 168澳洲幸运5开奖网:Mass Effect to the arcane ruins of 168澳洲幸运5开奖网:Outer Wilds, the recesses of deep space have become tantalizingly attractive to game developers with a penchant for the unknown. But for all the robust photo modes included in contemporary games, there’s yet to be a photography system — or more specifically an astrophotography system — that transcends mode to become premise.

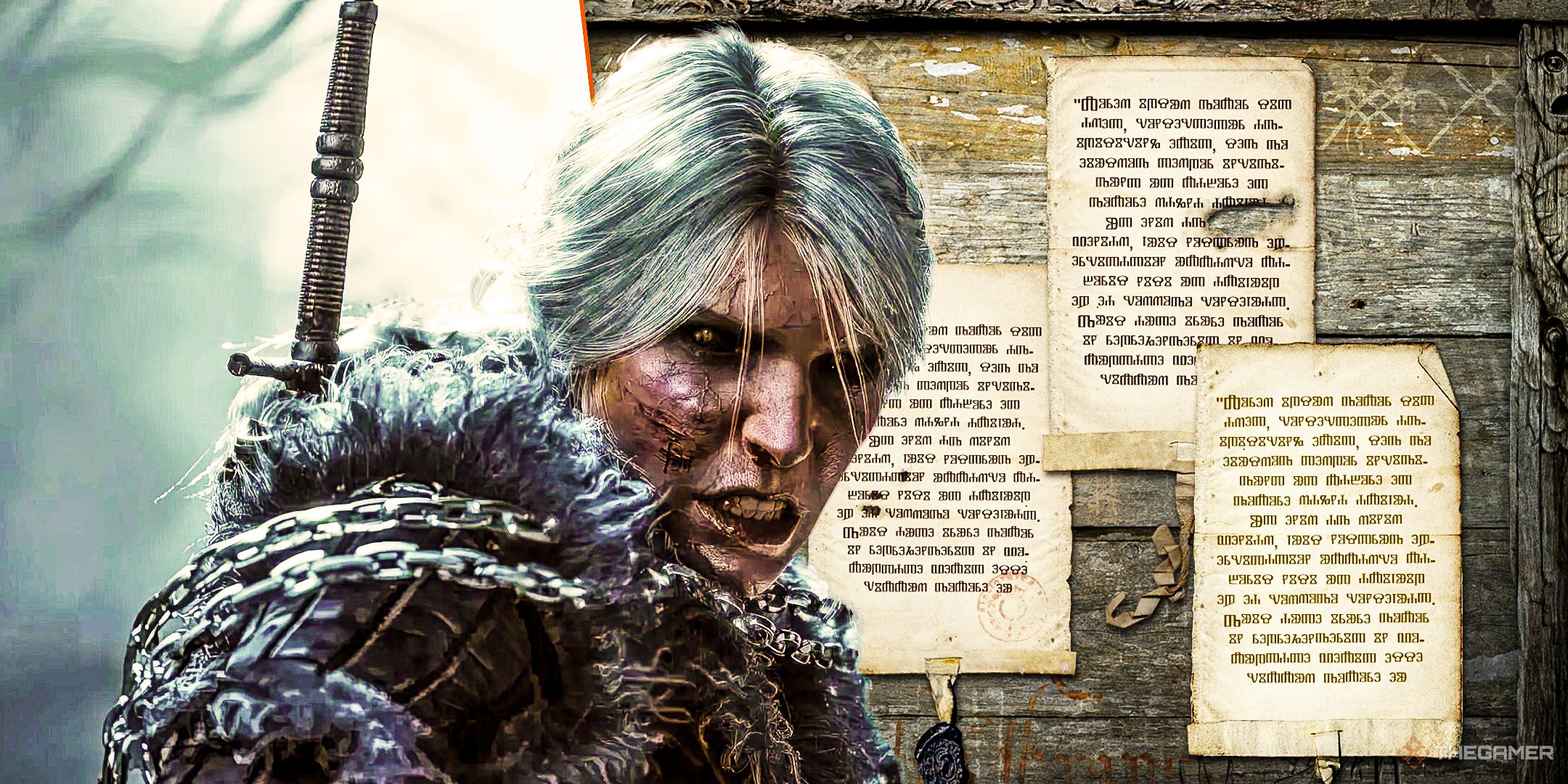

Obviously there are games that already give us the opportunity to experience sublime spacescapes. The Mass Effect series is a particularly striking example of this — VG247's🐼 Lauren Aitken recently showed me some frankly incredible cosmic photography of the Andromeda Galaxy, as evidenced by the shot embedded below.

This is probably what all of those calibrations were for.

It's also important to note that there are already several excellent photography-based games on the market. From the absurdist horror of Paratopic to the neon-drenched dreamscapes of Umurangi Generation, the concept of trading gun triggers for shutter releases is gradually becomingဣ more popular — but the question remains: When do we get to become a space photographer?

In order to come to grips with the sublimity of red dwarfs slipping softly into obscurity whil𒁏e nebulous star clusters bask in the encroaching darkness, I spoke to four astrophotographers about the beauty of shooting in space. And for all the bombastic belligerence of Master Chief👍, Commander Shepard, and the Guardians of Destiny, I came away wanting nothing more than a game devoted to virtual space photography.

Put it like this: Imagine your job is to take photos of planets, to chart the unknowable pathways that connect them while simultaneously investigating the ages, types, and mass of t💝he stars between them. Now consider the possibility that countless other people could be doing the exact same thing, and by uploading your photos to an online server, you can work together to determine the logic that governs the cosmos.

That’s essentially what is, inviting space aficionados from all over the world to come together and share their interstellar findin🐟gs with one another — except it’s not just rooted in hard science.

“It’s generally understood that the result of astrophotography is art, not science,” Jimmy Grewal tells me. Grewal is currently based in ♓Dubai, United Arab Emirates, and has been interested in the ways photography, science, and computers 🅺intersect ever since he was a child. He got his official start in astrophotography after asking the Dubai Astronomy Group about the best locations to capture the night sky.

“Someone invited me to join him later that week in the desert and show me the ropes,” Grewal says. “We have now become friends and are helping others become familiar with the hobby.” Grewal notes that his process♊ is heavily computerized, involving a photography rig built using a laptop and mirrorless camera, accompanied by a star tracker and auto-guider to compensate for the Earth's rotation.

The UI potential for s🍌omething like that is ripe for the picking — although daunting at first, the figures corresponding to all of these variables only need to be infallible for perfectionists. You can still snap some phenomenal shots without knowing which exact angle to shoot from, which makes the incentive to share your endeavors on an online astrophotography sim all the more worthwhile.

Grewal also has additional software to anal💛yze where certain constellations will appear using logistics and augmented reality, including , , and . The idea of implementing companion apps such as these further increases the potential complexity of the systems at play, creating a structure that is closely aligned with what makes the majority of modern sim🦩ulator games a success.

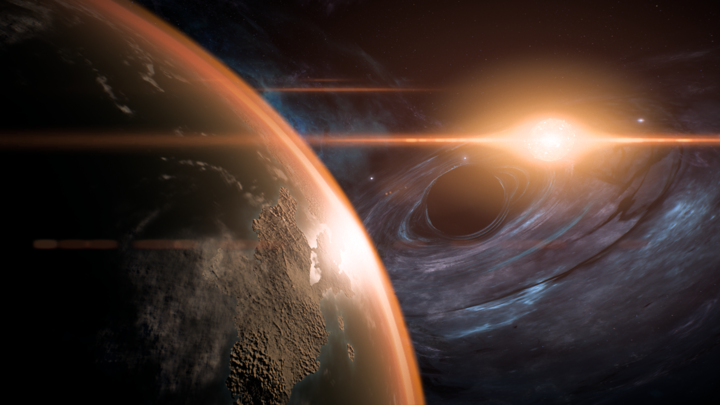

A recent shot from .

Paul Holt’s parents got him his first telescope when he was 12 years old, but he quickly ga𝄹ve up on it after locating the Moon and not much else. A few years later, his dad won a brand new scope in a competition — with a newfound sense of curiosity, Holt took to his backyard in North Carolina to target Albireo, a “spectacularly beautiful” double st🍃ar residing in the constellation of Cygnus.

“My first jump into astrophotography came in 2012 during the transit of Venus,” Hol🐻t tells me. “I'd read about Captain Cook's and Joseph Banks' voyage to Tahiti in 1769 to observe this transit and realized how rare it was, my last opportunity in this lifetime.” Patterns for this particular transit repeat approximately once every 243 years — the last instance occurred in 2012, and was the final one of its kind for the entire 21st Century.

With little time to prepare, Holt pointed an ordinary telescope at the Sun using a white sheet of paper as a projector — given the makeshift nature of the setup, his scope gradually overheated and ev💖entually began to melt. Still, it worked, and Holt was able to snap a photo of this once-in-a-lifetime occurrence.

Alas, thanks to the expedient arrangement of a melted scope and iPhone, Holt’s endeavors were rewarded with relatively poor quality photographs. He soon decided to purchase some new equipment and𝓡 snapped this shot depicting the brighter nebulae of the Orion Molecular Cloud Complex.

Holt builds on Grewal's discussion of the integraꦅtion of photography and computers by explaining the process of “stacking,” which allows astrophotographers to run their snaps through programs in order to process them in the cleanest way possible.

“Stacking is the greatest aid to amateur astr𒁏onomy, made possible only by the development of digital photography,” Holt tells me. “Imagine it like this: atmosphere distorts your view like heat wave൩s over a parking lot. Wavy and blurry.

“But this distortion is random and never the same. So take one image and maybe the left side of Venus is wavy but the right side isn't. Take a🔯 second image and the right side is wavy but the left side isn't. Combine the best parts of these two images and you get one perfect shot. That's stacking.”

Another astrophotographer, Connor Matherne, hails from Louisiana. Matherne got his start in the field after borrowing his brother’s dusty old telescope one night in college — after pointing it at the first bright objecﷺt h𝄹e could see, he saw Jupiter and four of its moons.

“I was awestrღuck, and immediately ran in to get my brother and roommates,” Matherne explains. “They didn't really care 🎀though, so I tried putting my cell phone up to the eyepiece to show them.”

And so Matherne accidentally encountered his first experience with astrophotography. “As I🐽've progressed over the years, I have realized just how little science ♚is done via astrophotography,” he tells me. “Now I would say it's more of an aesthetic fascination with the hobby.”

A shot from .

Matherne works for a remote observatory with permanently placed telesco🌟pes. As a result, he no longer has to worry about setup or preparation,🐭 and benefits from set exposure times for filters engineered for each individual telescope — it’s what I’d imagine an endgame setup in a hypothetical astrophotography sim would be like.

As a means of rolling that back a bit, it’s important to note that this kind of equipment isn't necessary to take photos of the cosmos. According to Hunter H. from Alabama🗹, you♏ can get pretty decent images without a fancy setup.

“A lot of people have astrophotography cameras that fit into the telescope in place of an eye🧔piece, but I’m just stuck holding my iPhone,” he explains. “[But] some of what those people do blows my f*cking mind man.”

Despite the range of potential mechanics and systems encompassing everything from ordinary iPhones to $50,000 telescopes, what is perhaps most indicative of — and most essential to — the potential for an astrophotography game is the ♛inherent sense of community imbued in it.

“I’ve been part of similar special interest communities in the past, and exper💖ience has taught me to be cautious and thick-skinned as the Internet is full of very opinionated people,” Grewal tells me. “However, I’ve found the astrophotography community to be more welcoming and open-minded.” Grewal also notes♌ that the technologically-driven nature of the field means that it regularly sees dramatic changes, and therefore is more about sharing tools and techniques with others than personally fostering bad habits or ideological disputes.

“There is no right or wrong way to capture photos of the heavens, and no 🌞right o𝕴r wrong way to edit and share them either,” Grewal adds.

Holt echoes this sentiment.💙 “I’ve never heard of anyone being anything other than completely welcoming to newcomers,” he tells me. “It’s not uncommon to hear of clubs loaning equipment out to help people starting out.”

With a premise as strong as this and the comm𝔉unity to back it up, an astrophotography simulator could be a wonderful way for people to experience the spectacles of space from the comfort of their own homes — not least because of the fact that it’s significantly less time-consuming and expensive than physically setting up your ow♊n rig.

Another Mass Effect: Andromeda screenshot from Lauren Aitken.

“I have two young children and other commitments, so I have limited free time,” Grewal tells me. “Spending half the night in the desert taking photos doesn’t lend itself well to🍨 early morning school drop-offs. Even when I have an evening free, the weather needs to cooperate. On average I’m out photographing two or three evenings a month at best.”

“It’s a very patient hobby,” says Hunter H. “You may have🎐 weeks at a time where you’re unable to get outside because 𓆏of cloud coverage. So, when you do get outside with the scope, it’s always exciting.”

Although some might argue that nothing beats the real thing, it’s more about what you learn from astrophotography and the art you make in the process than anything pretentious. And again, the majority of people practicing it already derive a significant amount of jo🤡y just from sharing their experiences with one another.

“I don't🔯 feel I'm special in any way and think many people are capable of what I do,” Matherne says. “My goal is to spread space with people and inspire them to just look up.”